Introduction

Surgical services are typically the most profitable area for a hospital. With revenues often exceeding two-thirds of a hospital’s total, these services have become the lifeline sustaining US hospitals in this turbulent healthcare market.

Unfortunately, the culture and management structure in many hospital-based settings for surgical patient care has not changed much over the past 100 years. This slow progress has made it difficult for many hospitals to adapt to current value-based payment models and do more to overcome current financial woes.

Some of the improvements in surgical care have actually exacerbated challenges facing surgical services. For example, an estimated 48.3 million ambulatory surgical and nonsurgical procedures were performed in the US in 2010. Of these, nearly 20 percent of surgeries were inpatient with overnight stays.1 The remaining procedures were performed in either surgical offices, ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) or outpatient departments. Indeed, noninvasive surgical technology, improved patient-centric care and revenue gain-sharing have fueled the continued out-migration of surgery from the hospital.

Hospitals are left with an increasingly sick and aging surgical population, worsening payer mix and demanding surgeons who ask for costly technology and better access. Meanwhile, the hospital must maintain its urgent care and emergency services, putting additional strain on both its staff and budget.

So how should hospitals address these issues? Some are engaging in relatively radical transformation that starts with the surgeon’s office and extends across the patient’s entire surgical care continuum. This transformation requires a new and novel collaborative process that includes interventions in leadership, operational management and process improvement.

Identifying the Obstacles to Surgical Services Transformation

While surgical services continue to implement new technologies and introduce new advances in care, the organizational structure and operation of these services have remained largely unchanged since the early 20th century. Hospitals now face a number of significant obstacles to transforming surgical services.

Organizational complexity

Hospital-based surgical, or perioperative, services often have a very complex organization—one that functions separately within the hospital. Compared with other services, surgical services often must acquire and manage some of the most expensive, sophisticated technology; satisfy a ravenous appetite for supplies; and employ some of the most highly trained (and well-paid) staff from a spectrum of specialties.

Individual teams that contribute to surgical services also work somewhat independently of one another. Preadmission testing, pre-op holding, the OR clinical staff, sterile processing and the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) often function as separate, siloed units, each with its own unique requirements and issues.

Human resource constraints

At the same time, staff requirements can constrain progress. Surgical services are often staffed by hourly employees who are regulated by clearly defined work rules and human resource department regulations.

Value-based payment models

Payment for healthcare services has traditionally been fee-for-service. Government and private insurers have paid the charges, with patients having very minimal exposure to cost. Recently there has been a shift, especially in the area of hospital-based surgical care: Bundled payments and outcome-based reimbursements are now rapidly replacing the fee-for-service model. These new payment systems have exposed several operating room issues and produced even more discord among OR clinical staff, surgeons and patients.

Surgeons and operating rooms: Strained relationships

Many surgeons have limited loyalty to hospitals. If the fragile relationship between a surgeon and hospital disintegrates, the surgeon could take patients to another institution. Although there is a significant trend toward hospitals employing physicians, there has not been much improvement in the strained surgeon-administration relationship.

Ineffective leadership and management structure

Traditionally, the director of the surgical service leads the surgical services team. The nurse director usually has wide-ranging responsibilities with limited authority and variable administration sponsorship or guidance. This director might have some anesthesia department assistance with operational issues, but the assistance can be inconsistent and poorly defined. Surgeons almost never take on leadership roles, other than in the usually ineffective medical staff or faculty-sponsored surgery committee.

The administration often functions in crisis management mode, responding primarily to the most vocal physicians and staff. As a result, many operating rooms struggle to provide cost-effective care with accurate documentation and consistent quality.

Driving a Value-Based Transformation of Surgical Services

Transforming surgical services requires hospitals to follow a new set of guiding principles:

- Gain a sound understanding of the time-tested business science of organizational transformation.

- Define a clear vision of the end state, including all the elements required in a value-based organization—such as high quality and low costs.

- Ensure that C-level administrators fully support and are willing to participate in the transformation.

- Assemble a select group of nursing, surgery and anesthesia team members who will work together to lead and manage the organization.

- Establish an ongoing database with appropriate analytics that measure the effectiveness of this transformation effort.

Hospitals should apply those guiding principles while intervening in three areas: leadership, management and process improvement.

Leadership

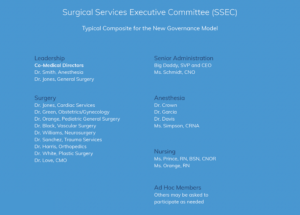

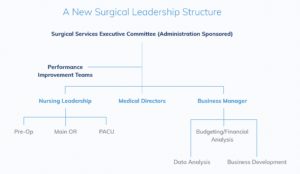

Leadership changes can entail the most significant departure from the traditional OR management structure. Hospitals should consider developing a unique team leadership approach for surgical services, creating a Surgical Services Executive Committee (SSEC).

The SSEC is a multidisciplinary leadership committee that acts very much like a board of directors for surgical services. Creating this committee can break down the entrenched and siloed culture, and bring about lasting organizational transformation. A well-run SSEC is the key to successfully meeting the challenge of 21st-century surgical care.

The SSEC should have a clearly defined structure. It should be “owned” and given its authority by the hospital administration.

It should have a different membership than traditional committees. The traditional hospital OR surgery committee comprises medical staff—a sponsored group of surgeons. This surgery committee usually concentrates its efforts on peer review and medical staff issues. Because it is a medical staff committee, it is not usually empowered to oversee or guide operations.

The SSEC should include four key stakeholder groups in surgical services: surgery, senior administration, anesthesia and nursing.

Senior administrators should include the CEO and/or COO/CFO/CNO. For optimal committee performance, these C-level representatives should be expected to attend meetings with the same frequency as all other members. In many cases, senior leaders will be eager to attend once they are exposed to the SSEC’s collaborative leadership style and lively, informative discussions. Drawing on the SSEC for strategic and operational direction can help leaders make better decisions.

Surgeons are the largest group on the committee. They should represent an appropriate cross section of specialties, and include both employees and private practitioners. General and orthopedic surgeons usually have the greatest number of representatives. The participation of surgeons in the SSEC helps bridge the gap between surgical needs and hospital priorities.

Nurses might include the director and frontline managers—usually two to three members.

Anesthesiology members usually include an anesthesiologist, who serves as a medical director (alongside a surgeon), plus one or two senior members in the department, such as the chairperson. We also suggest at least one certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA).

Medical Directors

The SSEC should have two co-chair medical directors: a surgeon and an anesthesiologist. Both of these important positions would be appointed by the administration. The surgery medical director would chair the meetings and work with surgeons on an as-needed basis. The anesthesia medical director, working alongside nurse directors and managers, would co-lead frontline operational management.

Mission statement

As with any organization, the SSEC should have a guiding mission statement—one that clearly defines SSEC goals. For example:

This Surgical Services Executive Committee is committed to providing an efficient, service-oriented and fiscally responsible operating room that exceeds the expectations of physicians and patients.

Oversight

The committee should be given oversight over all operations attached to perioperative services, from the initial scheduling of a patient to discharge from the recovery room. Governance goals should include:

- Improving surgeon and patient satisfaction

- Using accurate metrics, tracking appropriate data, setting benchmarks and building report cards that monitor and drive change and improve quality

- Increasing productivity and efficiency to reduce costs and increase profitability

- Enhancing communication and cooperation among surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses and senior administration

Management

Daily operational management is the second area of intervention for driving organizational transformation. The director of nursing, the nursing managers and the anesthesia medical director are the key players involved in improving operations at this level.

These team members should be able to spot the signs that an OR is not functioning at an optimal level, such as:

- High cancellation rate (day of surgery)— greater than 1 percent of the total volume

- Incomplete charts, which can cause delays and cancellations

- First case on-time start percentage (scheduled wheels-in time) is less than 85 percent

- Turnover times, even for simple cases, exceed 30 minutes

- Add-ons are greater than 10 percent of total volume

- High staff overtime and turnover rates

- Complaints that anesthesia is not available for many cases

- Daily stacking of add-ons occurs late into the evening

- Falling surgery volume

- Staff complaints of verbal abuse and inappropriate behavior of physicians or other staff members

- Low OR productivity/utilization (less than 75 percent adjusted utilization)

- Surgeon complaints about the scheduling office and limited availability for their cases

Close cooperation between nursing and anesthesia leadership is required for improving operational management. The anesthesia medical director should intervene in addressing:

- Chronic lateness and less-than-efficient room turnover, slow induction and emergence times, and so on

- Patient preparation, to ensure optimally prepared patients and charts

- Behavioral and communication issues

- Anesthesia department availability issues

- The relationship among surgeons, staff and administration

- Individual and department-wide quality/ clinical issues

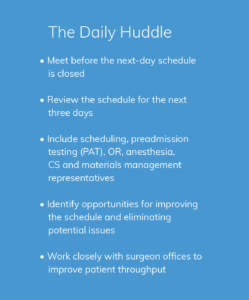

Nursing and anesthesia leadership should work together to manage the schedule proactively on a daily basis. The daily huddle is a key element in proactive management: It identifies clinical and operational issues up to three days in advance of the day of surgery. Participants can address preadmission patient preparation and optimization issues in the huddle.

Daily schedule management includes close cooperation with operational leadership, nursing directors, desk managers and others. Initially, it should be the responsibility of anesthesia operational leadership to intercede in the direct peer-to-peer liaison between anesthesiologists and surgeons. For certain surgeon-related issues, it may be appropriate for the surgeon medical director to conduct the interventions.

To measure the success of interventions, the SSEC can post daily insights, such as:

- First case on-time starts

- Cause of late starts

- Turnover times

- Completed chart percentage

- Flashed instrument percentage

The SSEC can sponsor change and operational management by helping to balance the needs of surgeons, patients and OR clinical staff. It can address a wide range of potentially contentious issues—outside of the OR.

Process Improvement

The third intervention area that is necessary for a successful perioperative services transformation is process improvement. Delivering better patient care and increasing throughput can have a significant positive effect on overall culture. Well-choreographed process improvement promotes productive, efficient collaboration among groups and units that previously were siloed and not functioning at optimal levels.

For sustained success, all process improvement efforts should be guided by appropriate analytics that track trends and measure progress against benchmarks and goals. Metrics should be posted as often as permissible— for example, the on-time start percentage should be posted daily. The majority of medium-to-large hospitals should have dedicated analytics staff members. Although it will require additional hospital resources to support this effort, the return can be substantial.

The performance improvement effort, organized into teams, should be sponsored directly by the SSEC.

Building Performance Improvement Teams (PITs)

Performance improvement teams (PITs) are critical for process improvement interventions. These teams should be built around defined segments of patient throughput. Examples of specific PITs include:

Scheduling and Patient Preparation

This team would review the current process from scheduling and patient preparation through the transfer of the patient to the OR. It would build new streamlined processes that reduce cancellations and delays while improving quality.

Process Optimization

This team would develop parallel processes for improving on-time start and turnover times, tracked by metrics posted daily.

Safer Surgery and Just Culture

This team would work to improve patient handoffs and time-outs, implement a daily huddle that prospectively reviews the schedule, and set standards of conduct.

Anesthesia Workgroup

This team would build a hospital-based, anesthesia-managed patient triage and preparation system to improve patient care and outcomes.

How do you design and manage a PIT? Using Scheduling and Patient Preparation as an example, here are some guiding principles for creating and maintaining an effective team:

- Assemble a group of key stakeholders. The PIT should include representatives from scheduling, the patient preparation unit, pre-op holding, OR staff, sterile processing, discharge planning, anesthesia and IT.

- Include frontline representation. The PIT should be populated and managed primarily by frontline personnel with assigned managers working alongside team members. It must be a “ground-up” approach to process improvement.

- Establish a charter. A charter should clearly define membership, scope of efforts, authority, ground rules of meeting management, goals and so on.

- Define benchmarks and goals. Make analytics an essential part of monitoring and guiding PIT progress.

- Act as ambassadors. Ongoing communication with the areas and staff affected by the PIT’s activity is necessary for successful OR-wide implementation. Each team member should be encouraged to act as an ambassador for the PIT, encouraging discussion and feedback.

- Roll out new processes. A pilot rollout can be an effective method for identifying issues before general implementation. A timeline with defined milestones can help keep the team focused.

Moving Forward in Challenging Times

Competing successfully in today’s turbulent healthcare environment demands embracing and implementing value-based patient care. This is especially true for hospital-based surgical care. Overcoming traditional obstacles and barriers requires an administration-sponsored leadership model such as an SSEC, which promotes collaboration among surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses and administrators. The SSEC sponsors and guides improved management of daily operations and enhanced patient throughput and services.

Resources

1 Margaret J. Hall, Alexander Schwartzman, Jin Zhang, and Xiang Liu, “Ambulatory Surgery Data From Hospitals and Ambulatory Surgery Centers: United States, 2010,” National Health Statistics Reports, No. 102 (February 28, 2017); https:// www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr102.pdf www.surgicaldirections.com