A strong labor and delivery (L&D) department is a key driver of hospital success. L&D not only contributes significantly to hospital profitability, it plays an important role in establishing and cementing patient loyalty. And as hospitals increasingly take responsibility for community health, an effective birth program can make a measurable impact on local healthcare costs and outcomes.

However, many hospitals struggle with managing the variable maternity population. This leads to problems with patient satisfaction, physician retention and referrals, and financial results. To avoid these problems, OR leaders should explore strategies for improving patient access to L&D, increasing department efficiency, streamlining mother and baby throughput, and optimizing clinical outcomes.

Get off to a good start

In a typical L&D department, high-risk deliveries are responsible for the bulk of quality and efficiency problems. The key to managing these deliveries is careful triage. In most hospitals, the anesthesia department is best equipped to lead the development of an evidence-based triage process. An effective triage system enables the birth program to identify high-risk patients and optimize them prior to caesarean section or labor induction. Key components of a strong system are described below.

Perinatal phone screen

All expectant mothers should receive a telephone-based screening at 32 weeks. The screening tool should include basic surgical risk factors such as body mass index greater than 50; known or suspected bleeding disorder, coagulopathy, or thrombocytopenia; history of anesthesia-related complications or family history of malignant hyperthermia; significant heart, lung, or neurological disease; and history of substance abuse disorder, including current use of Suboxone. In addition, the process should screen for problems specific to pregnancy and/or delivery:

- preeclampsia

- anemia (hemoglobin of 11.5 or less)

- obstetric complications likely to lead to operative delivery (such as placenta previa or multiples)

- severe edema

- anatomic abnormalities of the face, neck, or spine (stemming from surgery or trauma)

- extremely short stature, short neck, arthritis of the neck, or goiter

- abnormal dentition, small mandible, or difficulty opening the mouth.

Preadmission testing

Patients who answer “yes” to any of these screening questions should be scheduled to visit the obstetric (OB) preadmission testing (PAT) clinic. During the visit, an anesthesiologist or nurse practitioner should evaluate the patient and create a plan for mitigating any serious issues. For example, the OB PAT team can evaluate severe edema patients for possible blood clots or cardiac issues and address any medical problems prior to delivery.

Evidence-based lab matrix

The phone screen should also be linked to an organized process for ordering preoperative lab studies. For example, following an evidence-based lab matrix, patients with significant arrhythmias should be referred for an EKG, a prothrombin time/INR test, and a basic metabolic panel.

L&D departments can also use the scheduling process to identify issues that could hamper efficiency. Some departments have created a dedicated OB scheduler role. Schedulers who focus on perinatal care are better able to identify problems proactively and ensure compliance with state guidelines.

Most states do not allow elective scheduled inductions prior to 39 weeks. However, physicians sometimes lose sight of timing and schedule inductions outside of the guidelines. A dedicated OB scheduler not only books the procedure, but has the knowledge and expertise to verify compliance with scheduling guidelines as well as all other state and federal requirements.

Create an efficient room schedule

Most L&D departments can benefit from three improvements to the scheduling system:

- Reserve adequate block time for obstetric cases. OB blocks enable efficient utilization of nursing staff and obstetric equipment. Most hospitals could schedule one or two full obstetric blocks (7:30 am to 3:30 pm) per day, depending on anesthesia availability. As a rule of thumb, hospitals with 2,000 or more operative births per year should consider creating a dedicated OR within L&D. Hospitals under this threshold can usually accommodate operative birth volumes with obstetric block time in the main OR.

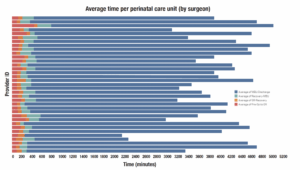

- Accurately estimate scheduled case times. In some hospitals, all caesarean sections (C-sections) are allocated a flat 2 hours of OR time. But this approach ignores surgeon variability. At one hospital we visited, scheduled obstetric surgery time was 35% to 40% longer than actual case time on any given day. We recommend using historical data to assign surgeon-specific case times for operative births. Consider using an Olympic average methodology: Identify case times for a surgeon’s last 10 C-sections, drop the high and low values, and average the remaining.

- Use predictive analytics to match capacity to demand. For example, heat mapping techniques can be used to create accurate demand models for obstetric surgery (sidebar, p 22). This enables OR leaders to optimize staffing by day and hour, right-size labor costs, and improve surgeon satisfaction.

Orchestrate roles in the OR

Efficient nursing processes can increase utilization and support surgeon productivity. Unfortunately, in many obstetric rooms, tasks are performed sequentially by key nursing staff. For example, the circulating RN might admit the patient, circulate the case, recover the patient, and transport the mother and newborn to the mother-baby unit (MBU). This approach is logistically wasteful because it prevents key processes from moving forward simultaneously.

Instead, we recommend assigning specialized RNs to work in parallel. Under this system, different nurses staff preoperative holding, the obstetric OR, the postanesthesia care unit, and transport, creating a coordinated system that minimizes downtime.

OR leaders should also analyze throughput to identify potential efficiency improvements. First, develop a tracking tool capable of time-stamping key milestones in the perinatal process. The goal is to capture time intervals for preop to OR, OR to recovery, recovery to MBU, and MBU to discharge.

Then examine the data for performance improvement opportunities for both departments and surgeons. For example, in many L&D departments, the largest variation occurs in MBU to discharge. Where this is the case, OR leaders can work with outlier surgeons and nurses to address the factors that are driving long stays in this unit.

Coordinate post-delivery care

Effective postpartum care is an important element of L&D performance. Most departments have an opportunity to reduce costs by optimizing postpartum length of stay (LOS). More important, high-quality care following delivery is essential to long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction. Several opportunities are available:

- ERAS for obstetrics. Leading L&D departments have achieved strong results by establishing Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols for caesarean delivery. Strong ERAS protocols might include early feeding for the mother, early ambulation, incentive spirometry to support anesthesia recovery, and an opioidsparing pain regimen.

- Service coordination. It is also important to coordinate post-delivery events for both mother and baby. Most hospitals do a good job of providing baby health screenings, fundal massage, breastfeeding classes, circumcision, etc, but these services are not tied to time-based targets. Creating time-stamped recovery milestones will help ensure patients receive key services in a timely manner and shorten LOS.

- Choreographed discharge. Mother and baby discharge processes require special attention. In many L&D departments, coordinating obstetrician and pediatrician rounds is a logistical challenge. We recommend creating a mechanism for enabling obstetricians to perform electronic discharge. In addition, some hospitals have created a “perinatal ticket to discharge”—a document that specifies which milestones must be achieved before mother and baby can go home. This patient education resource is an effective tool for motivating mothers to achieve recovery goals.

Postpartum care is complex, so there are many opportunities to make incremental improvements. Here are two additional strategies:

- Schedule inductions to start at midnight. When an induction starts at 8 am, the patient has already lost one-third of a hospital day. Starting inductions at midnight creates more time at the end of a stay for patient education, health screenings, and other important services. Very busy L&D departments in particular should consider this strategy. In our experience, patients do not have a problem with this approach.

- Add a home health nurse to the care pathway. Home health support can enable timely discharge of more mothers and babies. In addition, a home health nurse can be a strong driver of patient satisfaction with overall care. Establish integrated OB governance In many hospitals, the L&D department is led by nurse managers without strong input from other key players. To address this gap in leadership, some hospitals have created a formal advisory role for obstetricians. Although this is a step forward, it is an incomplete response to the problem. The best governance structure for a birth program will incorporate the full range of OR and OB stakeholders.

Some hospitals have established a Perinatal Services Executive Committee (PSEC). A PSEC is essentially a birth program board of directors that is sponsored by hospital administration. Physician participation is key, and a strong PSEC will have solid representation from obstetricians, OB hospitalists, anesthesiologists, and neonatologists. The committee should also include high-level nurse leaders (representing the OR, MBU, and NICU) and administrative leadership (including the chief executive officer, chief operating officer, and chief nursing officer). As a cross-disciplinary executive governance group, the PSEC is able to make high-level decisions about department strategy, access, and operations.

To be effective, the PSEC needs robust data on birth program performance. The solution is to create a dashboard report that clearly presents L&D performance on a range of clinical, operational, and financial measures. This can include department efficiency measures such as OB block utilization and turnover time.

OB PAT productivity can be tracked in terms of phone screens and patient visits (both gross volumes and percentage of patients screened or evaluated in person). For tracking quality, many leading departments use the perinatal nursing care measures developed by the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses.

Tackle big quality and safety issues

One of the PSEC’s key responsibilities is to sponsor significant performance improvement (PI) initiatives. Most hospitals have several opportunities:

- Gain department agreement on evidence-based protocols. For example, the PSEC might lead the development of a clinical pathway for non-urgent C-sections. This protocol could provide clarity on the roles and tasks that make up an orderly “decision to incision.” Another significant opportunity is to improve the department response to preeclampsia. The PSEC could establish criteria for patients at high risk for postpartum hemorrhage and develop an organized plan of management. The plan could include a drug regimen for maternal hemorrhage (drugs, dosage, order) and a massive transfusion protocol.

- Adopt models that provide more patient- centered maternity care. Specific opportunities include improving patient and family communication and redesigning processes to maximize skin-to-skin care. Some leading hospitals have worked to develop “gentle C-section” protocols. The goal of this multipronged strategy is to make operative birth more like vaginal birth in terms of atmosphere, family involvement, and mother-child bonding.

- Enhance patient safety systems. Many safety strategies are only possible through strong multidisciplinary leadership—for example, the High Reliability Organization (HRO) model. Key elements of the HRO framework include focusing on systems and processes, seeing failures as a chance to improve, and valuing diverse opinions and skills.

As part of an HRO initiative, the PSEC could develop a critical event simulation program. A well outlined schedule of regular drills will help make sure teams are prepared to handle low-frequency, high-impact events. Participation should be mandatory for all physicians, nurses, and other caregivers, both new and existing. Some facilities make safety drills a regular part of the educational curriculum, and all caregivers are required to meet a designated performance threshold to “pass” the requirement.